Digital Accessibility in Learning Design

Designing with accessibility in mind provides an opportunity remove barriers and empower learners.

What is Digital Accessibility?

In its broadest form, Digital Accessibility means we design our content and platforms to meet the needs of all our learners. It means that the people in our community, those with different needs or requirements are empowered and can be independent without being hindered by something that is poorly designed or implemented.

Digital Accessibility can be seen as a difficult thing to achieve – after all, the successful implementation of an accessible approach does not have a binary outcome. Digital Accessibility is relative to the specific individual and the specific context. With that in mind, there are specific standards to which we can measure or benchmark ourselves, but ultimately, these benchmarks purely enable us to provide a flexible approach. That flexibility is what enables members of our community to engage without obstruction.

The goal is access for all. We do that by making our content as accessible as possible. We try to remove the barriers to engagement. But we should remember that this isn’t always possible. People can have conflicting requirements and there will be situations that we can’t always anticipate. But the biggest accessibility issues arise when there is a lack of awareness of the common practices that result in something being inaccessible.

That’s not to say we should beat ourselves up when we are made aware of the challenges. It’s that we should be ready to listen to the requirements of our community and be ready to adapt our practice and approach to address these challenges. We do this by:

- Providing alternative formats,

- Updating the existing content or approach to address the identified (or reported) challenges,

- Implementing a Universal Design approach that mitigates the potential for challenges, and

- Listening to the community, their requirements, and taking appropriate action.

Accessibility Characteristics

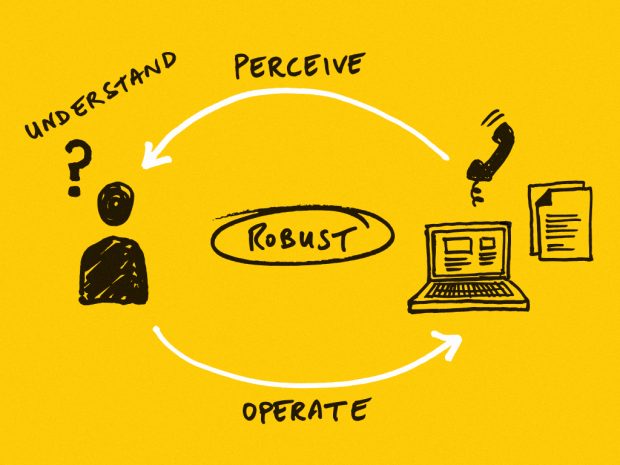

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3.org) has developed the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). These guidelines have become (one of) the go-to standards for Digital Accessibility. They’re organised around the following four principles. These are the necessary foundations for anyone to access digital content.

Perceivable

Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive. This means it must be available to at least one of their senses. For example, a text-based document can be perceived by someone with sight, but someone without sight will require this content in a format that allows for screen reader use, or electronic braille.

Operable

User interface components and navigation must be operable. In this instance, the content and platforms must be navigable through different mechanisms. An example being someone who uses the keyboard to navigate a webpage, rather than a mouse.

Understandable

Information and the operation of user interface must be understandable. Content and platforms should use consistent approaches in their design, plain English or appropriate imagery and ensure that the meaning of the content being presented is understandable by people with different requirements.

Robust

Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies. Consider a user of a screen reader, again. As the screen reader navigates across the page, does it read the content in the most appropriate order?

(source: https://accessibility.campaign.gov.uk/)

Addressing the Challenges

Often, we’ll design for the average person. But the truth is simple, there isn’t an average user. There’s a spectrum of needs across the community. We need to ensure that we deliver our content, platforms and services in such a way that we accommodate the range of needs that our learners have.

There are a common set of challenges that we should be aware of. These include:

- Visual: People who are blind need alternative text descriptions for meaningful images and use the keyboard and not a mouse to interact with interactive elements.

- Hearing: People who are deaf or hard of hearing will need captioning for video presentations and visual indicators in place of audio cues.

- Motor: People with motor impairments may need alternative keyboards, eye control or some other adaptive hardware to help them type and navigate on their devices.

- Cognitive: An uncluttered screen, consistent navigation and the use of plain language would be useful for people with different learning disabilities/impairments.

(Source: https://globalaccessibilityawarenessday.org/)

By considering these four categories and their unique requirements, we can start to design in such a way that mitigates the issues and starts to remove the barriers.

Removing the Barriers

So, what can you do to support the community? Here are some tips to embed accessible design into your practice:

Content Formats

Consider the formats in which you share content with your learners. Providing alternative formats, or accessible formats will enable learners to take ownership of their own learning.

- Alternative formats are considered a reasonable adjustment under the Equality Act (2010)

- PDFs can cause a multitude of problems for learners. Provide editable formats, such as a .docx or .pptx

- Note: PDFs do not protect IP and any modern Word Processor can convert a PDF into an editable document. But that doesn’t mean you should make learners take this action themselves.

- Use the inbuilt accessibility checkers in Office and Canvas

Captions/Subtitles

Whether you’re creating a video or holding a meeting in Zoom/Teams you should provide captions and subtitles. For videos (or meeting recordings) you may wish to provide a transcript of the audio. Captions aren’t just for those with hearing impairments, they can also be used to address the needs of learners with cognitive requirements, or learners who speak English as a second language.

- Turning automated subtitles on in Zoom

- Advising attendees how to use subtitles in Teams

- You can even add subtitles to your presentations when using PowerPoint

Automated transcripts aren’t always perfect, and some meeting attendees might not want them, in which case you can advise these attendees how to turn them off.

For videos, you should review transcripts and subtitles to ensure they are accurate. Remember, the video can exist for some time and a little bit of effort upfront goes a long way.

Writing Alternative Text (ALT text)

ALT text typically refers to a non-visible description of images which are read aloud by users of Screen Readers. Providing Alt text supports equality of learning experience. If ALT text is poorly written, then it does not provide an accurate representation of the image.

ALT text should typically:

- Accurate and equivalent in presenting the same content and function as presented by the image;

- Succinct. This means the correct content and function of the image should be presented as succinctly as is appropriate.

- NOT be redundant or provide the exact same information as text within the context of the image.

NOT use the phrases "image of ..." or "graphic of ..." to describe the image. It’s usually apparent to the user that it is an image. And if the image is conveying content, it is typically not necessary

ALT text can be difficult to write, take a look at the guidance from WebAim to learn more.

Understandable Design

Making something understandable can seem a bit abstract, but there are some simple actions that can help learners engage.

- Use diagrams and images to support the text

- Align text to the left (not centred, not justified)

- Use a consistent layout and make good use of the space available

- Provide reminders and prompts within the content

- Use bold to add emphasis, try not to underline or italicise

Being aware of and implementing Accessible Design

Nobody sets out to create inaccessible content. Many of the challenge’s users face come from a lack of awareness or knowledge. When it comes to accessible design, there are lots of simple changes that can be made to increase the accessibility of your content.

After all, Accessible Design is Good Design.

Photo by Sam Moqadam on Unsplash